As part of the Sackler Centre Residency Programme, Bettina von Zwehl spent the past year as an Artist in Residence at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. This unique experience, set within such a distinctive environment, has helped form her latest series of work inspired by the Museum’s miniature portrait collection.

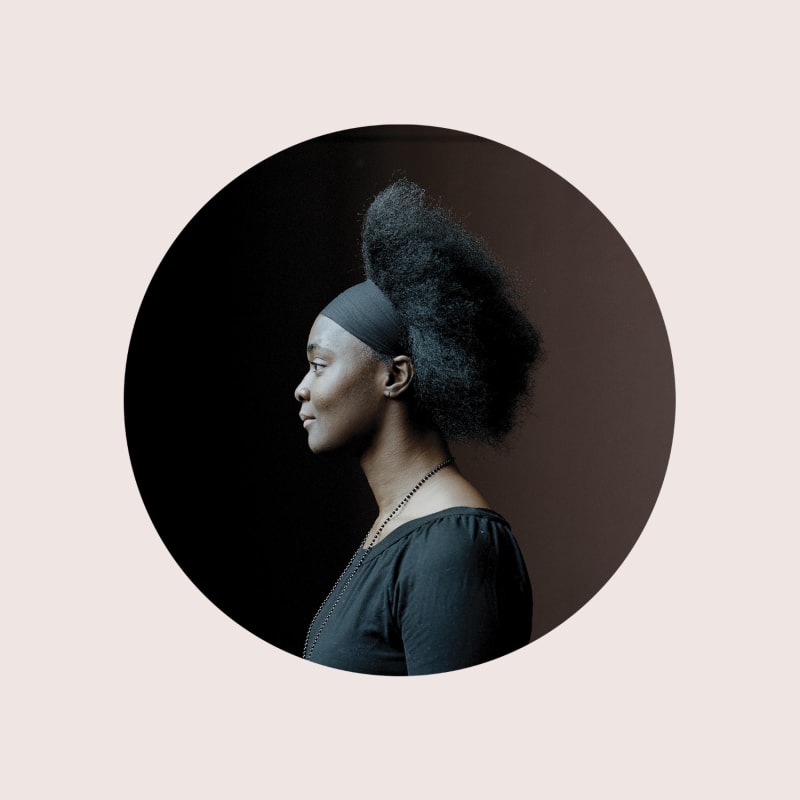

Bettina von Zwehl writes: Made up love song is a series of 34 miniature profile portraits, each showing the same female subject, Sophia, her face illuminated softly as she looks towards an unseen source of light, against the inky darkness of a background wall.

Made up love song is a culmination of a few interests and concerns that have been occupying me for a while, as well as a couple of coincidences. I’ve long been fascinated by the V & A’s collection of painting miniatures, especially those from the Renaissance period, and had been planning a small series of miniatures inspired by them. And then on one of my first days at the Museum, I came across this particular window - a window like no other, that seemed to emanate a glow all of its own - diffused, yet clear, and just amazingly beautiful - a giant soft-box, half way up a semisealed off staircase in the Northern Wing of the museum. And then I met Sophia…

As with my other projects, each image in Made up love song is characterized by certain fixed formal elements, so that on the surface, each image is strikingly similar to the next - yet this project marks an important shift in my practice; at the heart of Made up love song is a much more profound and engaged relationship with my sitter. I worked with Sophia, a Gallery Assistant at the V & A, over the six months I spent as Artist in Residence at the Museum, photographing her in the same pose, at the same location two or three times a week. It was an ongoing process of repetition and refinement, finding meaning and significance in the continual rehearsal and re-rehearsal of a moment, not just the taking of the picture, but the whole ritual around it, from Sophia and I meeting in my studio for coffee before the shoot, choosing that day’s outfit, and catching up with each other’s news before the staging of the photograph itself. As the months progressed, and we settled into our routine, we’d still find that each session would be inflected with a slightly different expression to the last – our moods shifted in themselves and in relation to each other, the pattern of the light changed, winter turned slowly to spring, and of course, each time we met, we were a few days older.

I am interested in how the portraits work both individually, and as a series. Some understanding of Sophia’s face has built up over time – but ultimately, the work has not been an attempt to reveal the ‘truth’ of her – instead it is much more a contemplation of her being in the moment, a celebration of the here and now.

Towards the end of my Residency, I found out that the glass in that huge window has not always been as it is today. Originally it was a magnificent stained glass window, designed by Reuben Townroe in the late 1860s, that had been destroyed during the Second World War.

Although in my pictures the window is never seen, and as a subject it remains hidden, somehow knowing about its history added poignancy to the work, and also to the time we’d spent there, working in that spot, in the stillness and quietness of that dusty, half forgotten place, where all that glass must have fallen. When the Residency was all over, and I’d packed up all my things, I went back one last time to see if there were any traces from the broken glass, scratches in the stone floor. All I found were the scuffed out chalk marks left by Sophia and me. Two separate marks; Sophia’s position and mine.